Равно как всякое альтернативное приложение, подвижное приложение GGPokerOk имеет свои сильные и слабые сторонки. Большая часть игроков вспрыскивают довольство интерфейса, высокую постоянство работы вдобавок сплошной перечень возможностей, подходящий ажно нате маленьких устройствах. Однако бирлять вдобавок интересные моменты, которые стоит дисконтировать передом задач как скачать ПокерОк получите и скачать покерок на ios распишитесь конура. Continue reading

Category Archives: Uncategorized

Should Someone Enter a Rebound Relationship Soon after a Breakup?

New research busts myths about the best advice for post-breakup recovery.

After a breakup, most young adults are often encouraged to take time to heal without rushing into dating again. After a relationship ends, broken-hearted partners may hear advice like “rebounds are an unhealthy coping mechanism.” However, in a recent 2025 peer-reviewed study in the Archives of Sexual Behavior, researchers reveal surprising results. The article suggests that getting involved with someone new after a breakup may actually be a positive thing.

The study, Breaking Up and Bouncing Back: Distress and Post‑Breakup Adjustment of Young Adults, examined over 800 young adults aged 18-25 who had just experienced a breakup from their romantic relationships. The authors, O’Sullivan, Belu, and Wasson, tracked how levels of self-esteem, distress, and intrusive thoughts changed if they stayed single or entered a new relationship. The findings were eye-opening, especially when psychotherapists usually caution clients from entering rebound relationships soon after a relationship breakup.

What the Research Found

The researchers conducted their studies using anonymous online surveys with young adults who identified as heterosexual, gay, lesbian, and bisexual. The authors discovered that the breakups were distressing for both partners, regardless of who initiated the breakup. The pain of heartbreak impacts both partners as the daily routines, emotional comfort and sexual connection have now abruptly ended. It is in the recurring and at times obsessive thoughts about the rituals and emotional experiences that cause partners to feel increased feelings of anxiety and a sense of being frozen.

The study found that people who stayed single after the breakup struggled more frequently with these ruminating thoughts and painful memories. However, the researchers in this study discovered that those partners who rebounded with a new relationship or situationship after a breakup were able to function more easily. While the subjects still experienced grief, the new romantic connection helped them with moving forward with their day-to-day functioning.

Additionally, the study reported that the rebounding partners’ overall well-being and confidence were greater because they felt desirable again. The study did not explore whether the rebounding relationship lasted a specific amount of time. However, they did discover a curious finding for therapists to hold in their clinical toolkit. The key to better functioning was not that the rebound relationship was going to lead to a new, longer-term relationship or marriage, but that it functioned more as a lifting out of the ruminating habit. The main cause of the post-breakup distress wasn’t the grief itself, but the intrusive and persistent thoughts partners continued to have about their ex-partner. The rumination and obsessions were what kept people stuck.

The Second Arrow: Why Rumination Hurts So Much

This finding aligns closely with the clinical teaching, the Buddhist concept of the Second Arrow, which I introduce to clients in my practice. In this parable, the first arrow that strikes a person is equivalent to a painful event, whether it’s a physical injury or a relationship breakup. The second arrow is what happens when one shoots themselves by adding in self-blame and the negative mental load.

To break free from it, one must not allow the cycle of negative thoughts to win. Naturally, when people go through a breakup, their mind often fills the silence with rumination. So, in therapy with post-breakup partners, teaching them to mindfully reduce their obsessive thoughts about their ex-partner, while still mourning the loss of the relationship, can be a critical therapeutic technique for their recovery.

A Both/And Approach to Healing from Heartbreak

Many therapists may still hesitate to encourage their clients to initiate a rebound relationship. However, the takeaway here isn’t recommending that heartbroken partners should jump into relationships in order to avoid processing their feelings. Therapists should be open to their clients starting to date while also using therapy to both mourn the past and not isolate themselves in obsessive thought loops.

Mel Robbins echoes this in her Let Them framework, articulated in her podcast and her book. She highlights the importance of no-contact periods after breakups. She even points out that things like “a revenge diet” because of an ex may cause a partner to remain too emotionally enmeshed with their ex. According to Robbins, in order to get over a breakup, a person has to untangle all the aspects of the previous relationship from the new reality. To rewire the brain away from shared routines and constant reminders. In her book, she says: “You have to unlearn your life with them so you can start living your life without them.”

How to Rewire The Post Breakup Mind

Clinically, this study reminds us that many clients struggle less with grief and mourning itself and more with psychological rumination. Interventions that reduce rumination, like cognitive reframing, emotional expression, and social connection, may be more impactful than focusing solely on “closure.”

Here are tips that will help clients mourn a breakup while rebuilding their lives.

- Don’t ignore and suppress your feelings

- Return to daily routines you did before the relationship to give a sense of stability

- Talk openly with supportive friends or family instead of isolating

- Join a support group for breakup partners

- Allow the feelings without feeding into obsessive thought loops

- Begin a daily mindful meditation practice to help battle rumination

- Avoid emotional discussion with your ex-partner if it’s a final break. Revisiting the decision isn’t helpful to either partners unless you and they are open to couples counseling.

- Don’t wait too long to start dating again; go out for casual dates to regain confidence and to have some fun.

Self-pleasure, dating, creative engagement, and new experiences with people can all help to disengage the mind’s rumination and get unstuck. Breakup recovery isn’t about waiting a prescribed amount of time before dating again. It’s about helping and supporting partners to move forward with a clear mind, rather than an obsessive one.

Audi: Intelligent Design in Motion

Audi stands out for its modern design language and technological innovation. The brand places strong emphasis on digital solutions, precision engineering, and high-quality interiors.

Audi vehicles are known for their stability and confidence on the road. The famous Quattro all-wheel-drive system enhances control in various driving conditions, making Audi suitable for both city streets and highways.

Audi appeals to drivers who prefer understated elegance combined with advanced technology and everyday usability.

Top Ten Sexy and Intimacy-Building Gift List for This Holiday Season

As the holiday shopping spree begins, here are a few tips for gift-giving:

- Focus on meaning, not the price tag.

- Prioritize shared experiences and connection over impersonal and trendy material gifts.

- Treat gift-giving as relationship care, not a burden.

Below are some of my favorite holiday gifts designed to be shared—either with a romantic partner or with someone with whom you’d like to build a deeper connection and vulnerability.

Each of these gifts highlights one or two of the 5 senses and/or emotional intimacy:

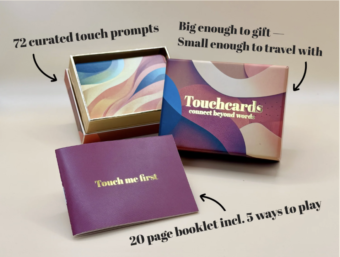

A poetic card game by Anne-Lorraine Selke and Jakob Wolski. 72 precise and playful prompts invite you to explore new ways to express yourself with touch. Play with lovers or friends, as innocently or intimately as you like.

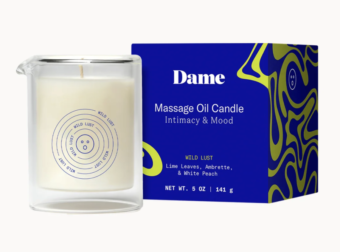

Massage candle (with delicious scents, so this gift covers touch and smell) sold by Dame, a respected woman-founded sex toy company. This candle provides an ambiance that turns into tactile, scented, warm pleasure when the candle melts into massage oil.

Lelo vibrator for male and female identified partners TIANI™ DUO is a dual-action couples’ massager featuring two powerful motors working in tandem, resulting in a dual sensation transmitted to the clitoris and the penis. Because it bends easily, it can be used by all body shapes, helping both partners experience synchronized mutual pleasure. The technology allows partners to increase the intensity of the vibrations with the flick of a wrist using a remote control.

While most people might remember when this original list went viral when it was written about in the NYT a few years ago as how to fall in love (I was interviewed about it here: https://www.cbsnews.com/video/the-36-question-experiment-for-creating-intimacy/)

The original study was done between people who didn’t know one another, and their attachment to their conversation partner was measured after they had asked and answered these questions. So this is not about falling in love solely, but how to actively create closeness with another person.

This company is known for its sex wedge called the Liberator. They also make a larger cushion for bigger-sized folks to provide them with extra support.

It’s so important that folks of all sizes have accessories, clothing, and toys that support them in their pursuit of pleasure.

UnboundBabes makes this vibrator that can be used in and on any human body, which is great for LGBTQIA+ folks. It is very bendable, can be used internally in a vagina and/or anus, or externally on other erogenous zones, and can be shared after a simple soap and water cleanup.

Become a human canvas for a human body artist like Andy Golub.

Or get playful and invite a friend or partner to do an art session (in a warm location) where you and a partner paint one another with body-safe paint. It’s a creative experience that tingles the visual, tactile, movement, and perhaps sound senses if you put on your favorite playlist.

A remote-controlled vibrator, which is a fun one for couples who happen to be apart.

The Skin Deep offers thoughtfully designed question decks (e.g., Couples, Co-workers, Friends, Parents) that invite emotional honesty and vulnerability. The questions are grounded, sometimes playful, sometimes deep, and can be used between partners or close friends to foster meaningful conversation and connection.

I like this toy because both heterosexual and queer couples can use it during a date to create a simmer in a flirtatious manner. One partner can control the sensations with the remote while the other wears the vibrator in their underwear, turning an ordinary evening into something playful and charged. I also really appreciate the store itself. One partner can use the remote to control the sensations while the other wears the vibrator in their underwear, bringing the vibe. I also love the store, which is private and owned by an experienced seller who is a wonderful advisor and creates a safe, comfortable experience for shopping at her store.

At the end of the day, the most meaningful gifts aren’t about the price or perfection; they’re about the intention. Whether it’s a conversation starter, a sensual object, or a shared experience, a good gift says, “I see you, I thought about you, and I want to connect with you.” It is especially important during the holiday season, which can feel hectic and lonely. Choosing gifts that invite presence, play, and vulnerability can help strengthen connection long after the wrapping paper is gone.

Three Tips for Holiday Gift-Giving and for Couples Wellness this Season

How to create more meaning of your gift-giving experience with your partner.

AnastasiaShuraeva

The holiday season of Christmas, Chanukah, and Kwanza can be filled with a lot of tasks: planning family gatherings, attending social obligations, confirming travel reservations, and of course, the expectation of purchasing and receiving gifts. While it is true that a gift can serve as an expression of love, many times it is bought in haste, along with so many other items on the checklist. This can then be felt as less meaningful to the partner who is the receiver, and does very little to provide emotional, romantic, and erotic growth to the relationship. Research shows that gifts aren’t solely a tradition, but rather, are great tools to help couples reconnect, show love, and strengthen closeness. Here are three frameworks to help spouses and partners buy a more emotionally attuned gift for their partner this holiday season.

Tip #1: Gift Giving May Be More Effective Than Speech

In a 2024 study in the Journal of Consumer Psychology by Howe, Wiener, and Chartrand, they found that receiving a small, thoughtful gift was sometimes more effective than a supportive conversation. The participants who received a gift from a loved one reported stronger feelings of being cared for, valued, and emotionally satisfied than those who were simply told kind words. This also aligns with research connected to the Five Love Languages framework. A 2024 study by Impett et al showed that when people rated each love language separately, more than 50% showed that gifts were one of the most meaningful ways they feel loved.

Additionally discussed by Howe, Wiener, and Chartrand was how crucial it was for the gift to be given intentionally and with the receiver in mind for it to hold such significance. The study specifies that this gift does not have to be something large or expensive; it can be as simple as a scented candle. A carefully chosen gift can reinforce one’s partner’s emotional presence and commitment.

Tip #2 Experiences or Objects — Both Can Work, If They Include Personal Meaning

When it comes to gift-giving, experiences are rising in popularity, and there is a reason for it. In a Journal of Consumer Research paper by Chan & Mogilner (2016), experiential gifts such as date nights, games, and trips are reported by participants as more effective than receiving objects due to the shared memories the experiences created for the participants. These shared meaningful experiences deepened the relationship in a stronger way than did material gifts. A client described how she created a scavenger hunt around the apartment she shared with her boyfriend, as she knew he loved this game. It ended with a gift card for a private session at a local karaoke bar he loved to go to with their friends. However, this same study also emphasized that emotionally evocative material gifts can also be powerful. These material gifts would include objects with meaning that carried an emotional resonance. When a client had a unique cake from a specific region of Italy delivered to his boyfriend as a holiday gift, his partner was so moved, as they had initially tasted it together on their romantic vacation the summer before.

Newer research reinforces the benefits of experiential gifts. Across three different recent experiments led by Puente-Díaz & Cavazos-Arroyo with college-aged students, the researchers found that experiential gifts (like events, activities, or shared experiences) make people feel more autonomy-support than material gifts. Autonomy support is defined as the feeling by the recipient that their gift feels like it aligns their particular preferences, individuality, and in essence “fits who they are”. Thoughtfully chosen experiential gifts evoke stronger feelings of being understood, respected, and valued.

This can readily be seen when the experience is actually not something the giver is that into, so in essence, the gift is very clearly a scenario that is solely for the pleasure of the receiver. A clinical example occurred when a wife relayed how she booked a reservation for an all-day spa day for her husband and her, despite the fact that she had never really been a huge fan of saunas and jacuzzis. She purchased it and took a day off work because she knew how much pleasure he’d get from not only the spa but the fact that she took the time and was there, sharing the experience with him.

In short, the intention, the alignment, and the sharing of the experiential gift to the receiver resonated as deeply than solely the gift itself. So whether an object-gift is a book the giver knows their partner will love, a bottle of sensual massage oil with an invitation to an intimacy date written on a heart shaped homemade card, or an experiential gift of an intimate relationship card game, intentional objects and experiential gifts like these have both been shown to be felt as more meaningful by the receiver than a costly but impersonal gift.

Tip #3 Gifts Are Relationship Wellness Experiences, NOT a Holiday Duty

What also makes gifts so powerful is their ability to express nonverbal loving communication and a way to tend to the wellness of one’s relationship. They can express care, support, validation, and playful passion, feelings that become even more valuable when so much of the verbal communication during the season gets drowned out by the noise of holiday logistics and planning. Gift giving is a way to enliven the erotic, romantic, and sexual energy of a relationship through the surprise and novelty of the gift, which are keys to the emotional and sexual wellness of every relationship. Rather than viewing gift-giving as a duty, expanding the concept of experiential and meaningful gifts is a critical strengthening practice for any relationship. Over time, these small gestures of attention and bonding can grow a couple’s foundation beyond trust, emotional safety, and openness to inspire spontaneity, flirtation, and sexual excitement.

Healing Intimacy: How Sex Therapists and EMDR Therapists Can Collaborate for Survivors of Sexual Trauma

Host: Sari Cooper, LCSW, CST, CSTS, Founder of The Center for Love and Sex

Host: Sari Cooper, LCSW, CST, CSTS, Founder of The Center for Love and Sex

Guest: Maggie Vaughan, LMFT, Founder of Happy Apple Therapy

🎙 INTRODUCTION

“Welcome to the Allied Professional Interview Series. I’m Sari Cooper, AASECT Certified Sex Therapist and Supervisor, and the Founder of the Center for Love and Sex in New York City. Today, we’re diving into a deeply important and often misunderstood area of therapeutic collaboration — how sex therapists and EMDR therapists can work together to support survivors of sexual trauma on their journey toward healing, intimacy, and pleasure. Joining me is Maggie Vaughan, LMFT and Founder of Happy Apple, an EMDR specialist who focuses on trauma-informed care and nervous system regulation. Maggie, I’m so glad to have you here today.”

Foundations of Healing Collaboration

Sari:

“Let’s start by grounding our audience. Maggie, for those who may not be familiar, can you briefly describe how EMDR therapy works and how it helps people process sexual trauma?”

Maggie:

“Absolutely. EMDR — Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing — helps clients reprocess traumatic memories that are stored maladaptively in the brain. For survivors of sexual trauma, it’s often about helping them reconnect to a sense of safety in their body while reducing the emotional charge of those traumatic memories. Once that groundwork is laid, they can start to experience intimacy and sexual pleasure without the same physiological or emotional reactivity.”

Sari:

“That’s so vital. As Certified Sex Therapists at Center for Love and Sex, we often see clients ready to address intimacy issues — pain during sex, avoidance, or panic and anxiety around being touched — when we assess and discover there’s unresolved trauma at the root. That’s where collaboration with EMDR therapists like you becomes essential.”

The Collaborative Process

Sari:

“Let’s talk about what a healthy collaboration looks like. When a sex therapist refers a client to an EMDR therapist — or vice versa — what are some best practices?”

Maggie:

“The first thing is establishing clear communication and consent. We want to make sure the client knows we’re part of a team — not two separate silos. Regular case consultation with the sex therapist (with the client’s permission) allows us to track progress, avoid overlap, and ensure that we’re pacing the work appropriately. Sometimes, EMDR treatment comes first to stabilize trauma responses; other times, we can move concurrently, depending on the client’s readiness.”

Sari:

“Yes, and from the sex therapy side, once EMDR has helped reduce the traumatic triggers, we can introduce sensate focus exercises, body mapping, and communication skills — helping clients re-engage sexually in a way that feels safe and empowering. This is true for clients who are single and want to date, as well as for people who are already in a relationship, partnered or married.”

Common Challenges & Misconceptions

Sari:

“What do you think are some of the biggest misconceptions Certified Sex Therapists might have about EMDR treatment, and vice versa?”

Maggie:

“Some sex therapists worry that EMDR is too intense or that it will ‘re-traumatize’ the client. In reality, EMDR is highly contained and client-led. We focus on resourcing and stabilization before we ever explore and treat the trauma directly. On the flip side, some EMDR therapists may overlook the importance of addressing erotic embodiment — which is where collaboration with Certified Sex Therapists becomes so powerful.”

Sari:

“Exactly. Healing trauma is not just about desensitization; it’s about re-sensitization in an empowered manner— helping clients reclaim pleasure, connection, safety and agency in their bodies.”

Integrative Healing in Practice

Sari:

“Can you share a case example — anonymously, of course — of how collaboration between EMDR and sex therapy led to transformation for a client?”

Maggie:

“Sure. I worked with a client who had a history of sexual assault and was experiencing panic during intimacy. Through EMDR, we targeted the traumatic memories that were still stored somatically. Once those responses softened, her sex therapist was able to guide her through body reconnection exercises and communication tools with her partner. The two therapies together allowed her not just to reduce symptoms but to rediscover joy and trust in intimacy.”

Sari:

“That’s such a beautiful example of integrative healing — how the trauma work sets the stage for the re-embodiment work that we sex therapists specialize in. From our end we have referred clients to EMDR-Certified therapist who had difficulty due to disassociation during sex and had only experienced sex as a giving, performative act for her partner’s pleasure rather than finding how to be somatically present and vocal about what she wanted for her own sexual pleasure. Through our holistic, collaborative approach she began to set up boundaries with her partner in couples work so that she could begin to discover what felt secure and physiologically stimulating in a sexual encounter.”

Takeaways for Clinicians

Sari:

“For clinicians reading, what are the top three takeaways we can offer when it comes to collaboration between EMDR Therapists and Certified Sex Therapists?”

Maggie:

“1️⃣ Build trusted referral networks.

2️⃣ Keep open communication with shared clients — with consent.

3️⃣ Approach this work with humility and curiosity. We’re co-regulating systems, not competing disciplines.”

Sari:

“Beautifully said. And I’d add — stay trauma-informed, become more sexuality -educated, and remember that healing sexual trauma is a team effort.”

Sari:

“Maggie, thank you so much for joining me today and for shedding light on the synergy between EMDR and sex therapy. For those watching, you can learn more about Maggie’s work at Happy Apple Therapy and about my practice at The Center for Love and Sex.

If you enjoyed this conversation, be sure to follow my Executive Interview Blog Series for more insights at the intersection of trauma, intimacy, and sexual wellbeing. Until next time — take care and stay curious.”

Feeling Stuffed But Not Satisfied: How to Manage Stress, Negative Body Image, and Create Space for Sexual Desire Over the Holiday Season Part 2

The Movember Movement Supports Men’s Mental, Body Image, and Sexual Health

Movember is an international charity that brings attention to major issues like men’s prostate and testicular cancer, mental health, and suicide prevention. During the month of November for the past twenty years, they invite men to grow a “mo” or mustache to raise money and awareness on illnesses that have long remained in the shadows. Each of these diagnoses directly impacts sexual functioning and relational health. Movember has added research showing that body image concerns, commonly associated with women’s mental health challenges, can deeply impact men too.

The results of a 2025 longitudinal study by Süleyman Agah Demirgül et al. in Sexuality Research & Social Policy echoed the Instagram study cited earlier related to women’s self body image. Following 3,700 young men and women, researchers found a bidirectional link between pornography use and body dissatisfaction only among men. Men who consumed more pornography at baseline reported greater Body Dissatisfaction one year later, and those that had higher levels of Body Dissatisfaction at baseline reported increased pornography use one year later.

The more pornography men were consuming, the more they developed concerns about their bodies due to the films’ unrealistic display of muscular physique and genital size. This led to not only self-criticism but also an avoidance of intimacy. When heterosexual couples come into treatment for therapy, there is a deeper shame in both partners when they report that the partner exhibiting lower desire is the man. Their female partners sometimes unwittingly contribute to the problem by believing the myth that all men have higher sex drives than women. For couples visiting family/friends or traveling over the holidays, the problem can worsen, privacy disappears and old family wounds can get triggered, leaving little space for desire or connection.

In a 2022 study, Moynihan, Igou, and van Tilburg found that when people, across genders, felt bored or emotional discomfort, they were more likely to turn to pornography for relief. In addition, men can also use pornography for entertainment and erotic/sexual release. With less privacy for masturbation, men who rely on frequent porn access might also feel emotional and physical tension and project it onto their partner over the holidays.

Men have been raised in a society that centers on a narrow range of acceptable emotional expressions that align with masculine ideals. While hegemonic masculinity ideals vary depending on racial, regional, cultural, and religious backgrounds, it might be a helpful tool for therapists to invite their male clients to check out Movember’s website as a conversation opener. Encouraging male clients to talk about how their body image, sexual desire, and intimacy behaviors might be impacted during the holiday season can be therapeutic.

From Critique to Connection

Some evidence-based strategies to help shift self-judgment into connection this season:

- Writing kind notes to oneself: This may sound silly, but it is shown to be effective. The Mindfulness study by Gracias & Stutts (2024) found that short self-compassion writing exercises reduced negative body image. Taking a few minutes to speak gently, self-reflection can really improve body satisfaction and mood.

- Movement for pleasure, not focusing on weight loss: Adding little things like walking, stretching, or dancing to one’s favorite holiday music can elevate dopamine levels and support the body without reinforcing a restrictive mindset.

- Intentional social media boundaries: To protect against unrealistic comparisons, take a step back from scrolling on social media and enjoy the time with loved ones.

- Ongoing communication about sexual needs and emotional vulnerabilities: Schedule time for open conversation, especially before the hectic holiday season begins, so each partner can express their needs regarding intimacy. Then look at the calendar to intentionally set times to be intimate during the holidays and define what that means for each partner. Honor that time so it centers and emotionally nourishes the mental health and relationship needs of both partners

While these may seem simple and obvious interventions, they do require intention, compassion, and planning. The holidays are filled with external noise, like familial expectations and potential judgments, so using a more curious lens as opposed to a critical one can really change the whole holiday experience.

How to Go From Feeling Stuffed to Feeling Sexually and Emotionally Satisfied

When one reports feeling “stuffed”, it is not only a physical feeling they’re describing but often an attempt to fill up emotional and sexual hunger with food, alcohol, substances, and/or distracting pastimes. True holiday nourishment doesn’t come from restriction or seeking perfection, but from authentic communication, rest, mindful eating, self-acceptance, and sexual intimacy (whether partnered or solo).

For women who are struggling with negative body image, it’s helpful to journal about what they truly desire over the holiday season. By carving out time and deciding what to say yes or no to, one can begin to practice sexual self-care. That might mean lighting a candle and taking time to reconnect with a person’s own pleasure, or setting aside intentional moments of touch and closeness with a partner.

Similarly, for men, Movember’s message extends beyond physical screenings. This serves as a reminder over the holidays that caring for the body includes planning ahead to care for the mind, emotions, and erotic and sexual pleasure. By the time the holidays wind down, sexual and emotional satiation often comes less from indulgence and more from feeling seen and authentically connected to oneself and to loved ones.

Feeling Stuffed But Not Satisfied: How to Manage Stress, Negative Body Image, and Create Space for Sexual Desire Over the Holiday Season: Part 1

While the holiday season is supposed to be filled with joy, connection, and lots of filling up on delicious holiday dishes, for many people, the pleasures fall short of their hopes. For some people, Thanksgiving and Christmas celebrations inspire stress, pressure to live up to family expectations, overeating to feed one’s emotional pain, along with psychological and/or physical isolation. Parents juggle restless kids in unfamiliar settings, hosts fret over creating “perfect” gatherings, and privacy can be hard to come by. Given the stressors of travel, pressure to ensure that everyone is ‘happy’, difficulty sleeping, and/or negative body image stirred up due to eating more than usual, these challenges can contribute to an overall body/mind/spirit feeling of “stuffed” and erotically and sexually unsatisfied.

According to a 2023 American Psychological Association survey, 43% of U.S. adults felt that the stress of the holidays makes it hard to enjoy them. In addition to that, a more recent 2025 study published in the Eating and Weight Disorders journal, Thomas et al. analyzed over 10 million social media posts that showed a body image dissatisfaction spike during this season. The study found that due to unwanted weight gain from the holidays, followed by New Year’s resolutions and fitness goals caused negative body-image issues. To strengthen this point, in 2023 Abdulan and his colleagues in Nutrients found that on Christmas, people ate 3 times their recommended daily calories with some meals coming out to almost over 6,000 calories.

Many therapy clients begin to experience anticipatory anxiety in early November as they begin planning for family gatherings, cooking and/or hosting responsibilities and the concerns around triggering old attachment wounds or trauma. If clients are already struggling in their dating, relationship and/or sex lives, figuring out how to sustain intimacy during Thanksgiving, Christmas, and New Year’s can fall way down on the list of other goals that are prioritized.

How Holiday Stress and Sleep Disruptions Impact Sexual Satisfaction and Functioning

Sex therapy clients report that when they travel for holiday gatherings, the first thing to get disrupted is their sleep schedule, which inevitably leads to less sex. While there’s plenty of research informing us of the importance of nightly sleep for overall mental health, there are even more disruptions during the holiday season due to several factors, including:

- Increased alcohol intake

- Children’s disrupted schedules

- Late-night conversations

The research backs up clinical observations. In a large wearable device study analyzing over 10 million sleep episodes, Heacock et al found that during major holidays, sleep regularity declined about 14%. That may seem subtle; however, in the Journal of National Sleep Foundation, Sletten et al. discovered that not only less sleep, but also inconsistent sleep can affect the body’s circadian rhythm. In their 2023 consensus, they found that having many different sleep times led to flatter cortisol rhythms and elevated stress.

In a 2019 Psychoneuroendocrinology study, Rosemary Basson and her colleagues discovered that lower morning cortisol can also be detrimental to one’s libido. More recent research echoes this connection between sleep quality and sex. In a 2023 study in the Journal of Psychosomatic Research, Pigeon et al. found that adults with poor sleep had significantly lower sexual satisfaction and higher rates of sexual dysfunction. The women in the study reported trouble orgasming and lower sex drive, and for the men, it was difficulty maintaining erections and lower sexual satisfaction.

Together, these studies show that disrupted sleep, which is very common during the holiday season, can dampen one’s mood, desire, and overall sexual pleasure. These problems contribute to less frequent sexual intimacy at a time when one may be in more need of that emotional closeness and tension release.

Why Women’s Negative Body Image Increases over the Holidays

Negative body image has always been a roadblock in women’s overall well-being and sexual desire, and pleasure. With the holiday season coming up, the challenge of internal body shame has the potential to increase. Between larger portions at holiday meals, endless photos for social media, the lure of diet culture, and relatives’ potential fat-shaming comments, many women report feeling torn between enjoying the food and celebration and fearing weight gain or self-loathing. Many sex therapy clients report being “in their head” during intimacy because of their internal body shaming, frequently comparing themselves to social media influencers who unrealistically portray society’s idealization of beauty standards.

In a 2024 study published in The Journal of Medical Internet Research, Anna Hinsch et al. investigated the relationship between Instagram use, self-criticism, and body dissatisfaction. Among the participants (90.2% of whom identified as women), those who spent over 3 hours/day viewing content centered around physical appearance exhibited higher levels of self-criticism and body dissatisfaction scores.

During the holidays, this internalized self-loathing can increase since social media platforms like Instagram and TikTok are flooded with photos of idealized tablescapes and holiday outfits modeled on ultra-thin women. Generally, this scrolling is continued during the holiday season as emotional regulation. Negative body image is associated with lower sexual desire, leading to decreased partnered or solo sexual activity.

World Mental Health Day: Why Sexual Health Must Be Part of the Global Well-Being Conversation

Every year on October 10th, the World Health Organization (WHO) partners with international organizations to bring awareness and support to people living with mental health issues on World Mental Health Day. According to the WHO, 1 in 8 people live with a mental health condition. Together with the World Association of Sexual Health (WAS), they recognize that sexual health AND sexual pleasure are a critical component of overall mental health throughout the lifespan.

While mental health disorders are being more understood by the general public because of their commonality, most people aren’t as informed about the frequency of sexual health disorders. In 2024, researcher Ramírez-Santos and his colleagues published a meta-analysis (a combination of many studies) in the Sex Med Review analyzing over 4,000 studies. They found that sexual dysfunction was prevalent in 31% of men and 41% of women, and these disorders were often linked to distress, depression, and anxiety. Unfortunately, many of these sexual disorders, like Erectile Dysfunction, low desire, Orgasmic Disorder (for women and men), and Genito Pelvic Pain/Penetration Disorder (GPPPD), were found to go underdiagnosed. This was due to many medical professionals lacking proper sexual health training in their residencies. Because their screenings were inconsistent, the researchers estimated that the true percentages are likely to be higher. When sexual disorders go untreated, it can lead to even poorer mental health. In their discussion, the researchers stressed that better screening and more awareness are needed to prevent the spike in mental health disorders and sexual dysfunction.

Another 2024 review of 63 studies by Vasconcelos et al. in the Bulletin of World Health Organization, also found that in almost all the studies, there were significant connections between positive sexual health and lower levels of Depression and/or Anxiety, as well as increased life satisfaction. These associations included men, women, older adults, pregnant women, and those in both same-sex and mixed-sex relationships.

As World Mental Health Day is honored on October 10th, it offers an important opportunity for therapists, medical professionals, and patients to explore how sexual health and mental health are interconnected. By making sure discussions about sexual health are not overlooked on this day, providers and their patients can gain a better understanding of what treatment is needed. This could include referrals to specialists such as:

- Certified Sex Therapists

- Doctors specializing in sexual health

- Pelvic floor physical therapists and/or

- Support groups

The Dual Link Between Sexual and Mental Health

As witnessed in sexual therapy clinical practice and in the professional literature, the relationship between sexual health and mental health travels in both directions. On one end, people who struggle with things like Anxiety and Depression tend to report having lower desire levels and more Anxiety when a partner initiates a sexual encounter. And on the flip side, people who struggle with sexual disorders report higher levels of emotional distress and sadness.

Daniele Mollaioli, PHD, and his fellow researchers published a study in the The Journal of Sexual Medicine illustrating the connections between mood and anxiety disorders and the subjects’ reports around sexual intimacy activity during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown period. Published in 2021, the study showed that people who maintained a healthy sex life during the lockdown were better protected from the risks of quarantine-related anxiety and depression in all genders.

While the pandemic was an extraordinarily unique and unprecedented time, more recent studies have also drawn the connection between mood disorders and sexual functioning. In a 2025 study published in the Journal of Affective Disorders, Chen et al. found that adults who had less frequent sexual activity issues with their sex life experienced significantly more depressive symptoms. Additionally, a study published in The Journal of Sexual Medicine by authors Dominguez-Bali and Hernandez, on menopausal women, highlighted the mental and physical benefits of experiencing orgasm, even through self-pleasure. This shows that there is no pressure to engage in frequent partnered sex to maintain sexual and mental well-being.

We can now see that in study after study, people’s mental health, especially symptoms of Depression and Anxiety, are strongly tied to their sexual health and satisfaction. In 2023, Pigeon et al., in The Journal of Psychosomatic Research, insisted that when people have healthy sex lives, they have better sleep, less stress, and fewer mental health issues.

The Impact of Sexual Stigma on Mental Health

In the modern digital age, Millennials and GenZers often brag on social media platforms like TikTok or Instagram about how frequently they are having sex. This trend, unfortunately, contributes to many sex therapy clients’ sense of failure about their own sex lives or lack thereof. However, in the sex therapy clinical setting, clients report that their most satisfying sex happens when they are relaxed, safe enough to express their authentic erotic selves, and are confident that each partner is fully consenting to and enjoying the experience. What most people truly need help with is developing their sexual agency or what this author refers to as Sex Esteem®, to practice an authentic, regulated, and differentiated way of communicating and listening to each partner’s needs.

Understanding that there is no one universal definition of a “good” sex life alleviates the pressure people feel to live up to a standard being depicted in sexually explicit media like porn, movies or social media influencers’ posts . For some people, it will be having sex less often, while for others, it can be exploring a new kink experience. However, there is one thing that stays consistent in all the research and clinical observations: when couples create a safe space and have clear communication in the bedroom, they are more likely to have a more authentic and pleasurable sex life, which can improve their overall mental health.

Identifying as a sexual minority can also be challenging for many people. The stigmas and threats of physical violence on the LGBTQIA+ community adds to their sexual and mental health concerns. When researching for the Clinical Psychological Science journal, Pachankis et al. found that people who experience sexual shame are more prone to Depression. There is a great need for more therapists and medical providers to be properly educated and trained in order to provide inclusive care to clients from sexual minority groups.

Steps to Care for Your Sexual & Mental Health

The WHO’s goal for World Mental Health Day on October 10th is to raise awareness and improve access to sexual and mental health education and services for those in need.

Here’s how you can care for your own and/or your partner’s mental AND sexual health:

- Visit psychotherapy or healthcare practices that offer specialties in sex therapy, sexual health education, and sexuality informed medical treatments.

- Ensure your medical provider and/or therapist initiates discussions on sexual well-being AND mental health status.

- Keep yourself informed about the latest in sexual and mental health research, updated treatment guidelines, and share this education with others who might also need to learn.

When mental health and sexual care are seen as integral components of overall healthcare, rather than distinct silos of concerns, people are more likely to feel physically, emotionally, sexually, and psychologically healthy.

How Do Sexual Identity and Orientation Labels Impact Therapy Clients?

This Pride month, cities around the globe celebrate the wide expanse of sexual identity. People honor the labels many use to identify themselves. Identities like gay, lesbian, bisexual, or queer are written on posters and floats, indicating the long hard-earned rights to declare who they are to the world. Beyond the hardships many of these folks are now facing in America, the therapy world needs more insightful education to help clients explore nuanced experiences in their sexual lives. Research suggests that difficulties in defining and categorizing sexual orientation can have negative implications for many individuals and/or partners in general. Psychotherapists, couples counselors, and medical professionals are in need of deeper knowledge to better serve their patients.

Sexual Identity Labels Often Don’t Fit

A 2010 study by the National Defense Research Institute states that the research on sexual orientation often relies on three main categories of definition – sexual/romantic attraction, sexual behavior, and sexual identity (self-labeling) – which frequently do not align into one clear label. This puts people into labels that don’t fit exactly right, which runs the risk of ignoring the diversity that plays a huge part in sexual identity development.

Lisa Diamond, a renowned psychologist working in sexuality, gender, and intimate relationships, discusses the differentiation between labels, thoughts, and actions. She states in her 2016 study in Current Sexual Health Reports that rates for same-sex orientation are highest when measured by attraction, followed by behavior, and lowest when based on self-identity. In a separate study in 2019 by the Journal of Official Statistics looking at these intersections, 9.1% of self-identified gay women, 3.9% of bisexual women, 8.4% of gay men, and 14.3% of bisexual men report being exclusively attracted to the opposite gender, which contradicts their sexual identity.

Clinicians must recognize that their clients’ sexual identity cannot be exclusively described in simple labels. Therapists who quickly place clients in prescriptive identities may show unconscious assumptions which can cause harm.

For some time now, sexuality researchers have been identifying men through their sexual behaviors versus labeling their identities. They label men who have sex with men as “MSM” versus “gay” or “bi”. This began most likely in the late 1980s by HIV and AIDS researchers, as many men who identified as heterosexual shared sexual encounters and behaviors with other men but did NOT identify as gay or bisexual. Separating the sexual behaviors from identities let researchers glean information as part of their battle against an epidemic crisis which at that time was causing a large number of men to die and the medical providers without an effective cure.

The Impact of Therapists Misusing Labels

This lack of clear categorization and the non-alignment of attraction, behavior, and identity among people can create internal conflict. In the article Sexuality and Gender: Findings From the Biological, Psychological, and Social Sciences, researchers Mayer and McHugh state that there can be a pressure to be “sure” about one’s identity and to adhere to the “born that way” hypothesis, creating a fixed biological basis for sexual orientation. If a client feels unsure about their sexual orientation, they may feel pressure to identify themselves with one exclusive label in order to feel accepted and supported by their community.

This pressure to conform is linked to mental health challenges. The article Sexuality and Gender by Lawrence S. Mayer et. al. discusses higher rates of poor mental health for LGBTQ+ individuals generally and explores the adverse consequences of concealing aspects of one’s identity. While labeling can have negative mental health effects, expressing thoughts and feelings is linked to improved well-being. If a clinician assumes and uses labels with which a client does not align, it contributes to the client feeling less open to sharing more complex feelings and attractions to their therapist.

Comfort Discussing Sexual Material in Sessions

The Journal of Marital and Family Therapy in 2008 published a study of 175 clinicians assessing how their training, education, perceived sexual knowledge, and comfort with sexual material influenced their willingness to engage in sexuality-related discussions with their clients. The findings stated that Marriage and Family Therapists who perceive themselves as having higher levels of sex knowledge were not more likely to initiate sexuality-related discussions. In fact, perceived sexual knowledge did not have a significant effect on sexual discussions in the path model.

Their results indicate that the combination of sexuality education AND supervision experiences are the cornerstone for a therapist’s base level of comfort. This is how sexuality knowledge is gained. When therapists I teach and/or supervise tell me they consider themselves sexuality-educated based on their lived experiences or having volunteered for a college peer program, I know that this isn’t enough to have productive, comfortable therapeutically effective sessions with clients around their sex lives within their clinical exchanges. It requires supervision that teaches the deeper understanding of the biological, medical and sexual health issues that intersect with therapy clients’ lives whether they are no matter their relationship status or identity.

Using Label-Free Language

I encourage the therapists I train and supervise to use neutral words or phrases to describe sexual behaviors with clients and emphasize that they understand it might be difficult to share these sensitive subjects. Using terms that aren’t labeled allows more openness for the client to discuss and explore often conflicting and overlapping fantasies, behaviors, and identity. Instead of asking: “Have you had any gay/lesbian/queer relationships?”, I encourage my therapists to ask: “Have you ever had any same gender emotional, sexual or erotic experiences growing up?” or “Have you had fantasies about a person that presents as a transgender?”. These gender descriptions of the person with whom they shared a sexual behavior or fantasies does not make assumptions about the client’s self-identity or orientation.

Therapists must get more didactic education and supervision to learn neutral language to use with their clients about sexual fantasies and experiences. It is through in depth training that all therapists and medical professionals can allow clients to feel more authentic with themselves in their psychotherapy journey and within the therapeutic relationship.